Beneath the shadows of three worn wooden windows, an ancient board declaring 'Urdu Bazar' stands deserted, cloaked in a veil of dust, telling the long-forgotten tale of Kashmir's Hafizas—dancers who became prostitutes.

Urdu Bazar finds its roots in Akbar's invasion of Kashmir when the rule of Kashmir's last native king, Sultan Yousuf Shah Chak ended.

The Mughals had their eyes on Kashmir right from the beginning of their rule in India in 1526. They first tried to seize this Himalayan country during Babur's time, who was the founder of the Mughal Dynasty, in 1528. After many failed military attempts over fifty years, the Mughal army finally occupied Kashmir in 1586. They snatched away its independence, turning it into just another province of their empire.

Unlike its counterparts in Delhi and Karachi, this Urdu Bazar bore no linguistic significance in Kashmir; instead, it earned notoriety as the stage for lascivious revelries in its brothels, hosting the infamous "Rangeen Shamein" night parties.

Fateh Kadal, once renowned for its handloom, woodcarvers, and artisans during the Sultanate period, evolved into the epicenter of Mughal entertainment.

Historian Zareef Ahmad Zareef recounts, "Mughals established these markets to make their nights colorful.”

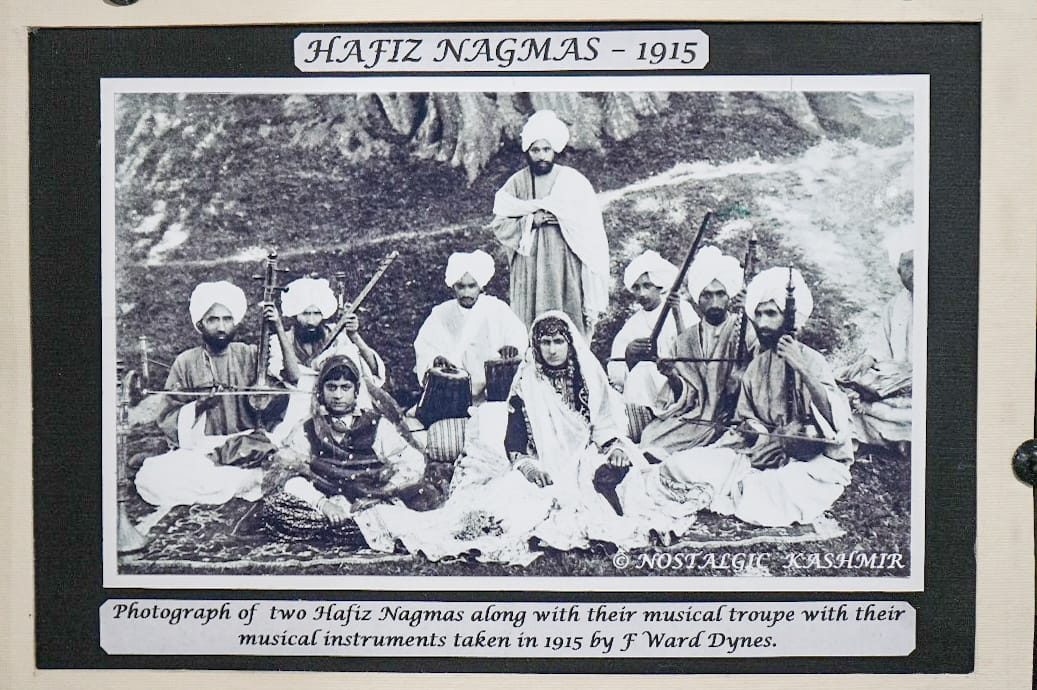

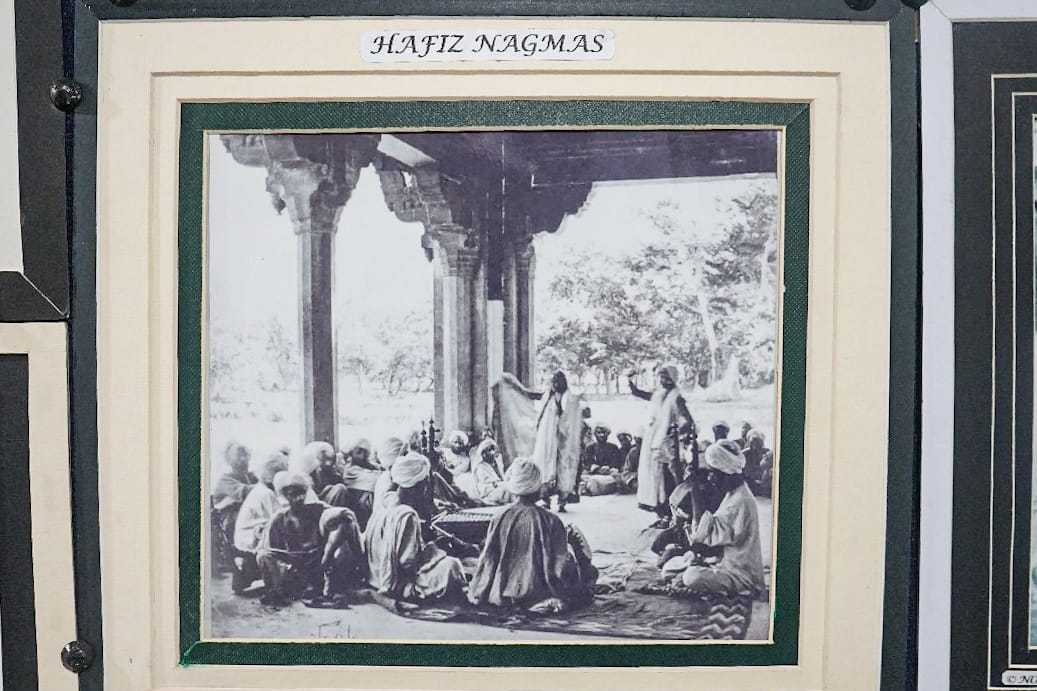

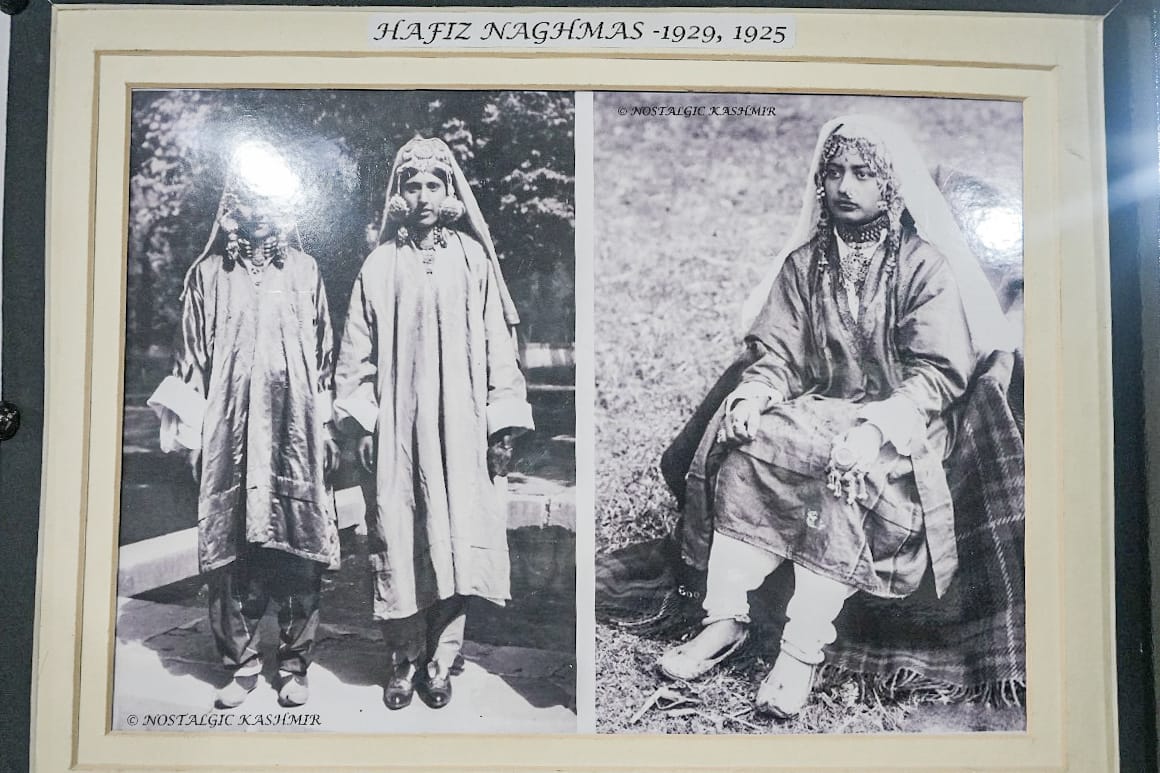

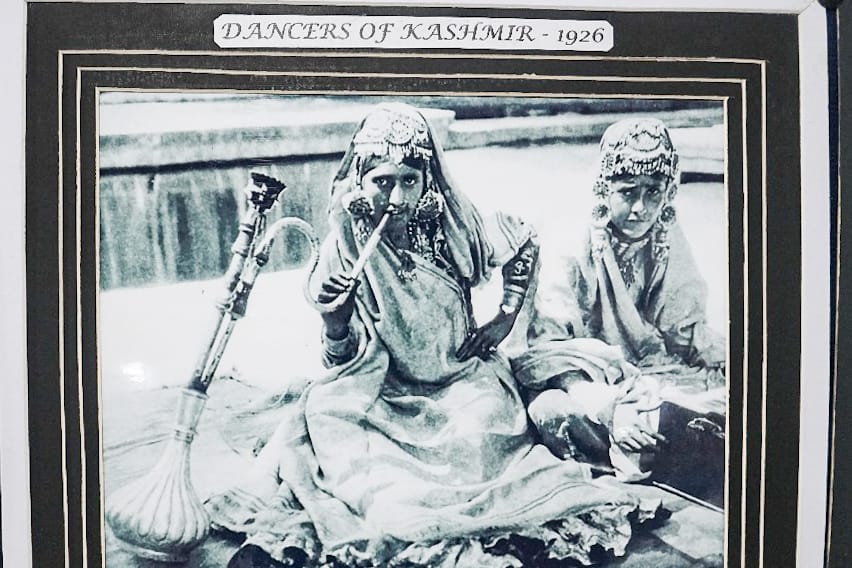

Brothels and bars emerged, featuring women initially known as "Hafiza," revered dancers, who eventually succumbed to the degrading label of prostitutes, Zareef Tells The Himalayan Post.

He explains that these places, known as "Gaani-Waan," housed these fallen dancers.

The roots of prostitution in Kashmir extend through the corridors of time, with historical references dating back to kings who patronized courtesans. Kashmir’s native king, Sultan Sikander reportedly banned prostitution in his kingdom, but it was the Mughals who, across successive eras, not only sanctioned but formalized the practice.

They designated specific localities dedicated to the prostitution, a trend that institutionalized during the Afghan rule and endured until the Dogra rule.

With the arrival of Afghans in 1753, the Urdu Bazar's brothels were relocated to Maisuma, Gawakadal, and Tashwan.

Under the Afghan Governor Amir Khan Jawan Sher, this trade was institutionalized, exporting both men and women to Afghanistan.

The Dogra Rule exacerbated the situation with heavy taxation on these women, turning their plight into a lucrative revenue stream for the state.

During the 1880s, Robert Thorpe records that the Dogra regime derived a major portion of its revenue—15-25 percent—from the exploitation of these women.

It was in the 1930s that Mohammad Subhan Hajam, a rebellious barber from Srinagar, emerged as a crusader against prostitution, Zareef adds.

In his memoir, Tyndale Biscoe, a stalwart in Kashmir's education, recounts the unsettling experiences of Subhan, known as Subhan Naevd, who resided in Maisuma. 'Nights for Subhan were filled with disturbing sounds - ribald songs accompanied by harps and zithers, the stridency of men arguing. Yet, what truly shook him, according to Biscoe, were the anguished cries of those thrust into a harsh existence, often young souls sold under the guise of arranged marriages by their own kin.'

Subhan penned pamphlets and poems, exposing the nefarious trade and distributed them widely in the city. Alongside a friend, he took to the streets, loudly preaching against the vile trade during the day and standing vigil outside brothels at night to deter the customers.

Undeterred by attacks orchestrated by pimps and their hired goons, Subhan faced false charges in Srinagar courts, a vendetta masterminded by the influential red-light area chief, known as “Khazir Gaan,” spared no expense in corrupting police officers to silence Mohammad Subhan Hajam.

Despite relentless terrorisation, Subhan's crusade gained traction, earning support from all sections of society—Muslims, Pandits, and Sikhs alike with judiciary acquitting him honourably from all accusations.

It was Molvi Mohammad Abdullah Vakil who, championing Subhan's cause, brought the issue to the forefront in the Praja Sabha (assembly) in 1934, advocating for legislation to shutter the houses of prostitution in Kashmir and the Dogra government, under immense pressure, passed "The Suppression of Immoral Trafficking Act."

Many women, ensnared in this trade found solace in handloom or secured employment in the silk factories of Srinagar.

Urdu Bazar, the birthplace of the Hafizas and witness to their tragic transformation, with Subhan Naved’s resistance remains a poignant reminder of a bygone era where the indomitable human spirit, though tested by tragedy, left its mark, quietly echoing through the corridors of history.

All the photographs were captured by Zubair Hameed during a photography exhibition held in Srinagar