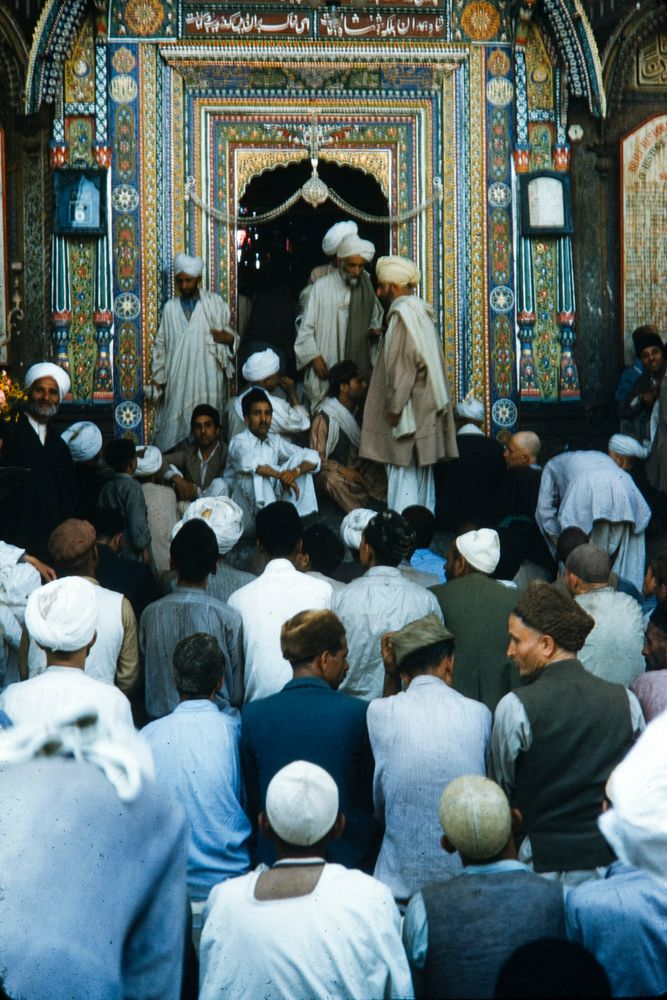

Kashmiri shrines have historically been shared spaces. If history is taken as a guide, then the ownership of Khanqahs - the religious convents dedicated for the propagation of Islam in the valley - becomes too complex an issue for one religious group to stake an indivisible claim over them- often to the exclusion of others.

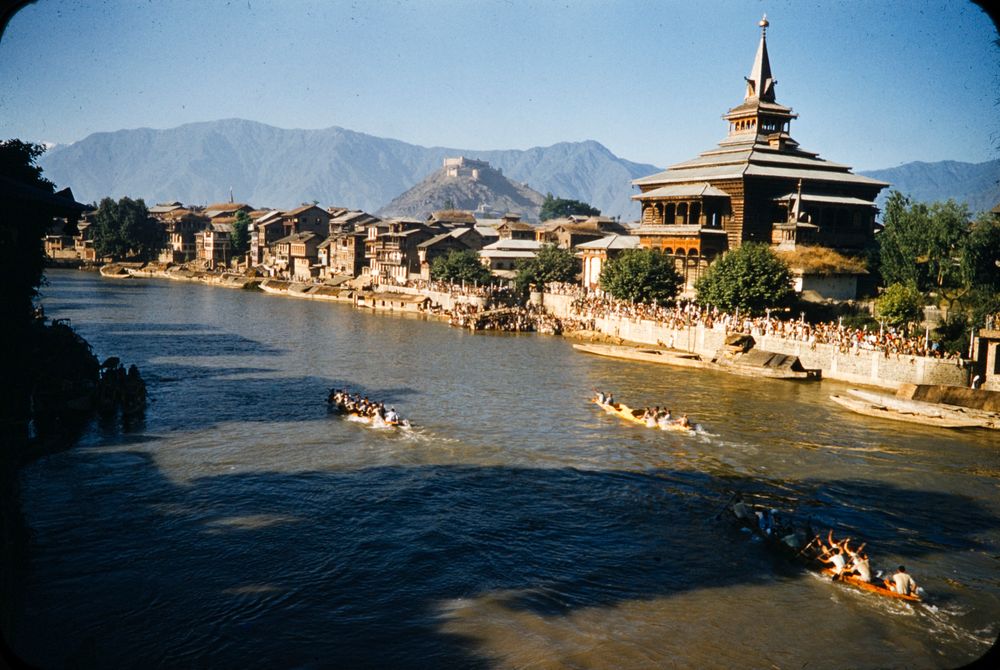

Photo Credits: Posh Bahar

Photo Credits: Posh Bahar

This time, the controversy erupted after a group of Shi’a mourners took an unusual detour from their daily itinerary in the holy month of Muharram when they were busy enacting various mourning rituals, and decided to enter Khanqah-e-Moula in Srinagar. A video which went viral on social media showed a group of young men dressed in the customary black beating their chests while reciting nouhas- laments that commemorate the killing of Hussain ibn Ali, the grandson of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad.

The row that followed appeared to suggest that the Sunni community - which commands the custodianship of Khanqah - was offended over azadari or physical acts of mourning being performed inside the sanctum of the shrine. Some religious groups have lodged the protest, alleging that an effort was afoot to undermine the sectarian peace between the two communities. But such protests are based on a very narrow understanding of Islam’s history in Kashmir, and tend to assume that two sects have emerged independently of each other.

The shared origins

Although Shi’ism in Kashmir started to emerge as a prominent force in the 16th century, the origin of the sect’s propagation in the Valley is as old as the story of Islam in Kashmir itself. In his exhaustive book on the Shi’as of Kashmir, scholar Hakim Sameer Hamdani traces the association of Kashmiris with Shi’ism back to 10th century, when Yakub al-Kulyani, a prominent collector of hadiths (saying of the Prophet) mentions of a meeting taking place between Mehdi, the twelfth Shi’i Imam, and Abu Sayeed Hindi, a Kashmiri adventurer.

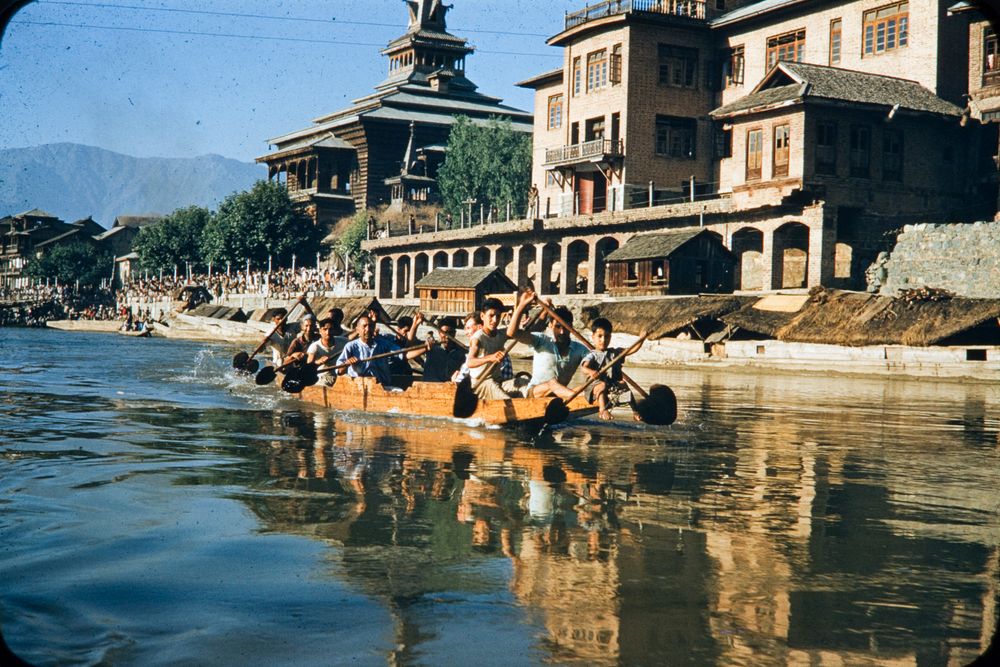

Photo Credits: Posh Bahar

Photo Credits: Posh Bahar

Another anecdote that features in Baharistan-i-Shahi, the 400 year old Persian text, refers to a conversation between Rinchana, the first Muslim Sultan of Kashmir and Bulbul Shah, a Sufi preacher from China who converts him into Islam. The narration in Shahi, which is the first source for this claim, is saturated with the praises of Ali ibn Abi Talib, the first Shi’a Imam. Today, the shrine of Bulbul Shah is a Sunni place of worship, but the distinct articulation of its origin story - rendered with Shi’ite symbolism - serves as an example to understand how the two communities inherit a shared history.

The question of legitimacy

It is only in the 16th century that the Shi'a sect appears to have risen as a prominent social and political force with the ability to sway the nobles and the viziers of the royal court, who are Sunnis. That happened after Shams-al-Din Araki, a preacher associated with the Nurbakshi Sufi Order came to Kashmir as an emissary of Timurid court centered in Herat, Afghanistan. Araki was swiftly able to win the favour of the Kashmiri nobility, and his missionizing activities accelerated after his second visit which came nearly 12 years after his first departure from Kashmir. From Afghanistan, he brought golden-rimmed robes for Sultan Hasan Shah, the then reigning (Sunni) monarch of Kashmir.

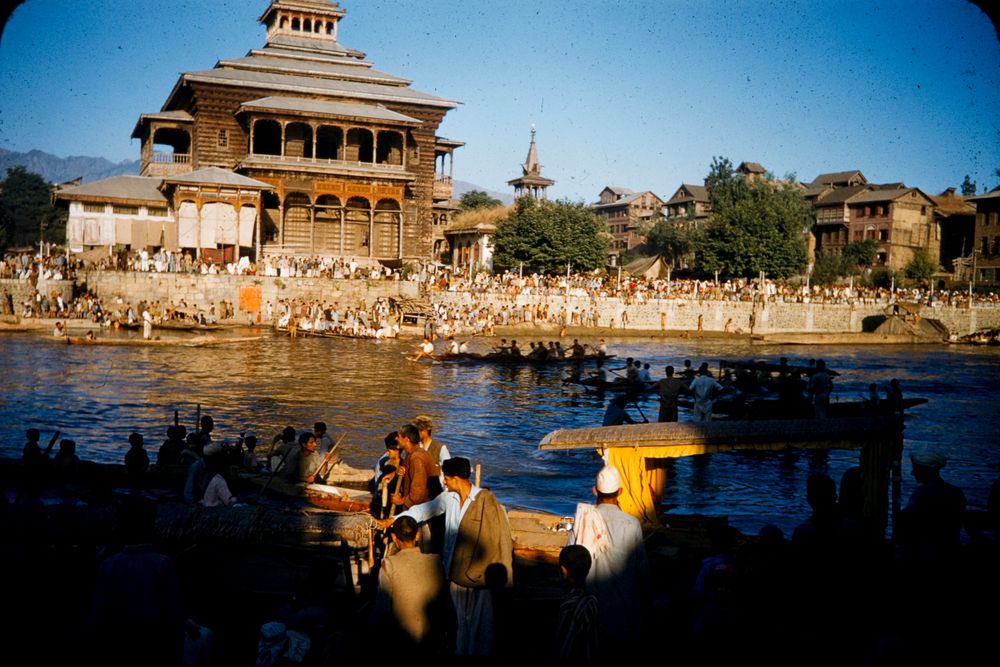

Photo Credits: Posh Bahar

Photo Credits: Posh Bahar

The discursive material associated with the Nurbakshi Order in Kashmir is even more interesting. Composed in the 16th century, Tuhfat-ul-Ahbab is partly a historical, and partly hagiographical account of Araki and his exploits in Kashmir. Going by the contents of Ahbab, it appears that the message of Nurbakshis resonated with the people of Kashmir because they projected themselves as a remedial force that would restore Islam to its true glory in Kashmir.

In their worldview, Islam’s original vigour had been undermined by Zayn-ul-Abidin ‘Budshah’, known for patronising Hindus and their religion. Instead, Nurbakshis made his father, Sultan Sikandar (again, a Sunni king), their supreme ideologue.

The Sunni patrons

Written by an anonymous Shi’a author in 17th century, the contents of Baharistan-i-Shahi, also suggest that his patrons were the Bayhaqi Sayyids, a group of Sunni immigrants who came to Kashmir from Khorasan province of Iran to escape being persecuted by Timur in late 14th century.

Shahi, while recounting the journey of Sayyid Mahmud Baihaqi, senior most in the tribe, from Iran into India also mentions of a dream he had at the shrine of Imam Reza in holy city of Mashhad when Ali, the first Imam, appeared before him and moistened his finger with the saliva before rubbing it on his lips.

Mahmud interprets the dream to mean that Ali had vested him with a mystical mission. He became a renouncer and his remaining family continued to propagate the values of the Kubrawi Sufi Order that was brought to Kashmir by Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani.

Reverence for holy relics

This brings us to another dimension pertaining to the symbiotic interactions between different Sufi orders in Kashmir. The more we dig deeper into the history, the more it starts getting clear how the histories of both these sects are more intertwined than previously known.

The tarikh of Sayeed Ali, another 16th century text that sheds light on the spread of Kubrawi monastic codes of Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani in Kashmir, refers to the flag standard (alam shareef) of Ali ibn Abi Talib that was part of Ali Hamadani’s investiture paraphernalia.

When Hamadani passed away after winding up his brief tour in Kashmir, the flag standard, as per the author, was handed over to a group of Kashmiris accompanying his corpse at Pakhli in Pakistan. This relic, associated with the first Sh’ia Imam, is then housed inside the Khanqah-e-Moula. Shi’a mourners have a history of visiting Khanqah on notable occasions and paying homage to the alam.

Further, the 1395 AD endowment deed of Khanqah, signed by Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani's son, reveals that its management was handed over to one Mulla Sayeed, who was a Shi’a- soon after the shrine was first constructed in the 14th century. The descendants of Mulla Sayeed are still around, and based in Srinagar.

Legitimate claims on shrine

Ahbab also produces a copy of royal farman (decree) issued in the name of Sultan Muhammad Shah (a Sunni king) in which he awards the custodianship of Khanqah-e-Moula to Araki, after he returned to Kashmir during his second visit. Nurbakshis later rebuilt the shrine on a bigger building plan and also purchased the land around the mosque so that it doesn’t catch the fire from the burning neighbourhood homes as was previously the case, according to the contents of Ahbab.

As for the remainder of its existence, the management has rested with the Sunnis. If the history of proprietorship of Khanqah-e-Moula - as well as the history of Islam in Kashmir itself - is defined by such a sectarian ecumenism, then it should continue to stay that way. The objection to the performance of mourning rituals inside Khanqah, thus, probably stems from a sense of misplaced entitlement.

The author is a freelance journalist based in Srinagar. He was previously a correspondent with the Times of India