Days after the Raj Bhavan acceded to the demand of Yuva Rajput Sabha, Kashmir’s noted scribe Umer Maqbool started a new debate — the genesis of which lies in the spirit of India’s freedom struggle.

“Declaring holiday on Maharaja Hari Singh’s birthday is regressive and against the spirit of Indian freedom struggle fought against not only Britishers but also against their puppet Maharajas of princely states,” Umer tweeted. “What if all erstwhile princely state subjects demand such holidays?”

While many are still wondering about the query of the journalist calling himself “state subject of princely kingdom of Jammu & Kashmir”, the resurrection of the regal as a new official holiday has created a hushed debate in the region.

Before calendarizing him, the demand for holiday on the eve of birth anniversary of Maharaja Hari Singh was gathering momentum with an agitation of Yuva Rajput Sabha in Jammu.

“This is not an agitation of Rajputs in Jammu but a demand of every single Dogra who include people from Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Christian community and from all castes of these religions,” Yuva Rajput Sabha said.

“Maharaja Hari Singh is the man who did all good things in Jammu and Kashmir and brought reforms in education, banking sector and he is the one behind accession of J&K with India. This [agitation] can snowball into a major controversy if J&K LG administration ignores the genuine demand of the people of Jammu.”

Sensing the growing grumble in the province where Bhartiya Janta Party made a clean sweep in 2014 elections, LG Manoj Sinha acceded to the demand. And days later, the Hari Singh became another official day-off in J&K.

But between the Maharaja’s dramatic fall and rise, his legacy is still dictating the politics of the region.

Maharaja's diehards celebrating his day in jammu

Maharaja's diehards celebrating his day in jammu

When the public holiday list for 2020 was issued by the Government of India in December 2019, several political parties in Jammu including Congress demanded a public holiday on the birthday of the last king of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

The pitch shrilled when Kashmir Martyrs’ Day observed on July 13 was dropped and October 26 was added as Accession Day in the list.

Soon the J&K administration formed a four-member committee, headed by principal secretary, administrative secretaries of social welfare and culture department and the divisional commissioner of Jammu, to commemorate the Dogra ruler — whose regime saw the movement of ‘Kashmir for Kashmiris,’ anti-Dogra uprising, rise of Kashmiri political presence, Jammu Massacre, Poonch revolt, Tribal invasion and Accession.

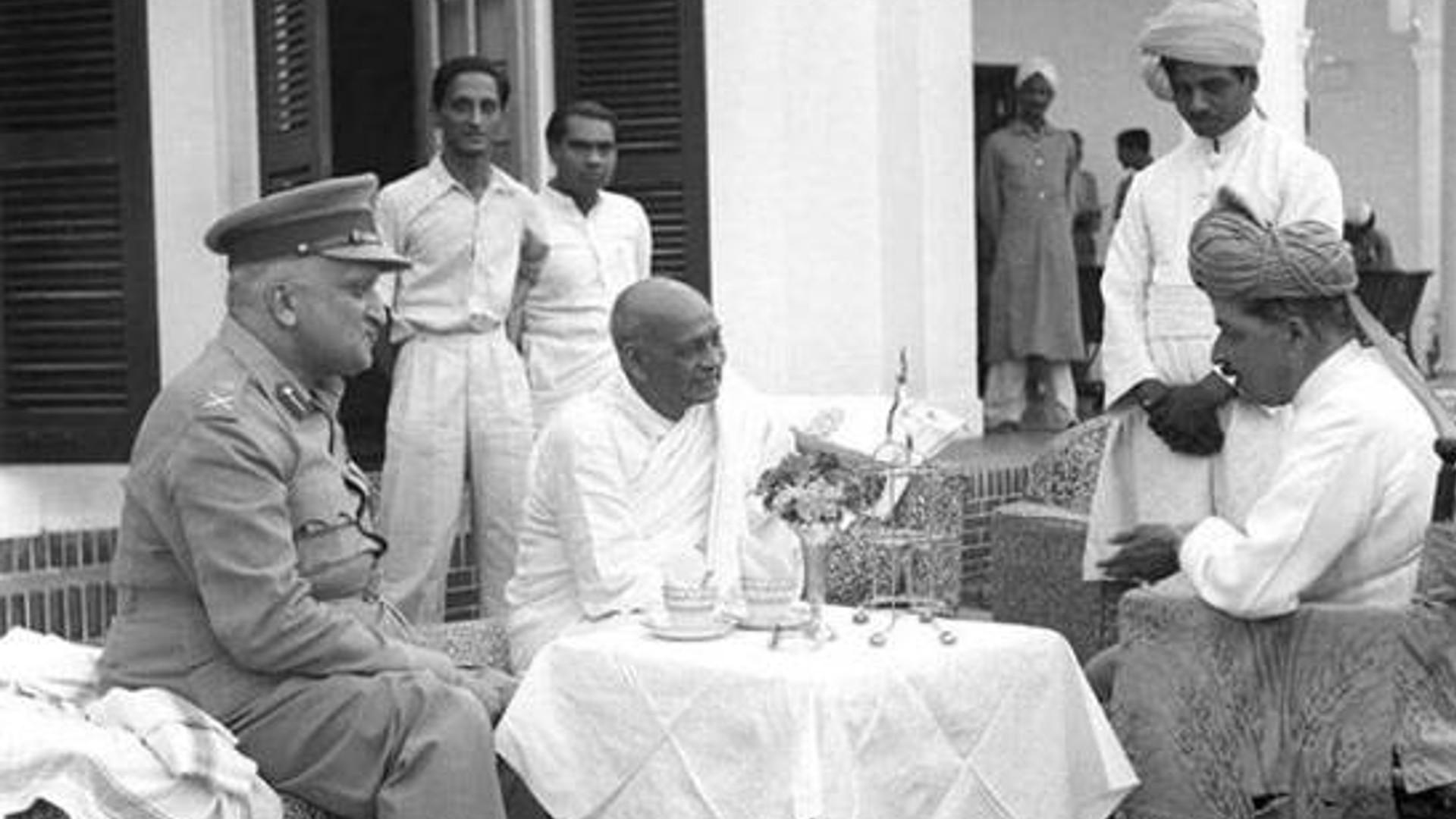

Hari Singh with Indian leaders

Hari Singh with Indian leaders

Born on 23th September 1895, in Amar Mahal Jammu, Hari Singh ruled the princely state till 1947. He was son of Amar Singh who was the son of Ranbir Singh, who in turn was the son of Gulab Singh. The brazen purchase of Kashmir by Gulab Singh in March 1846 remains the most harrowing auction of a nation ever.

Taking oath as the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir in 1925, Hari Singh made state subjects—dissolved now—mandatory for acquiring government jobs or immovable property in J&K.

According to historians, the monarch’s move to bring ‘outsiders’, mostly from Punjab, in government services triggered a movement—‘Kashmir for Kashmiris’—by Kashmiri Pandits.

“The issue of who should be administrators of J&K became grave, even the then Muslims were subjugated as lesser citizens,” writes historian Victoria Schofield in her book, Kashmir in Conflict.

The uprising forced the king to pass a law, ‘Hereditary State Subject’, in April 1927. It forbade the employment of non-locals in the public services and purchase of land in J&K. Only locals from Jammu, Kashmir, Gilgit, Ladakh, Baltistan and Poonch were given these rights.

“The second challenge to autocratic rule occurred in 1931 when Kashmir mounted a serious anti-Dogra uprising in the valley,” writes Christopher Sneden in his book, Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris.

“In Srinagar, the Reading Room Party, comprising several graduates from Aligarh Muslim University in British India, rose to prominence. Prem Nath Bazaz, Ghulam Abbas and Muhammad Yusuf Shah were all active in discussing their grievances.”

It was a time when Kashmir was already like the proverbial powder keg, Victoria Schofield notes in her book. “An alleged desecration of the Holy Quran by a Hindu policeman in Jammu worked as the catalyst.”

In response to the sacrilegious act, butler Abdul Qadir made a fiery speech in Srinagar’s Khanqah-e-Moula in July 1931, calling for the people to fight against oppression. His subsequent arrest made masses to throng the central jail in Srinagar. In the ensuing police firing, twenty-one people died and the day came to be known as the Martyrs’ Day in Kashmir.

In the deadly din of 1931, a young Kashmiri—Sheikh Abdullah—took over the political grounds in J&K. His secular beliefs would later motivate him to rename his political party from Muslim Conference to National Conference. His ideals also brought him closer to the first Prime Minister of India, Jawahar Lal Nehru.

Mirroring Gandhi’s Quit India Movement in 1942, Abdullah launched a Quit Kashmir Movement against Hari Singh’s Dogra rule and faced prison. Fearing protests, the crown-administration placed the state under martial law. Other prominent political activists, including GM Sadiq, DP Dhar and Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad, escaped to Lahore, where they remained until 1947.

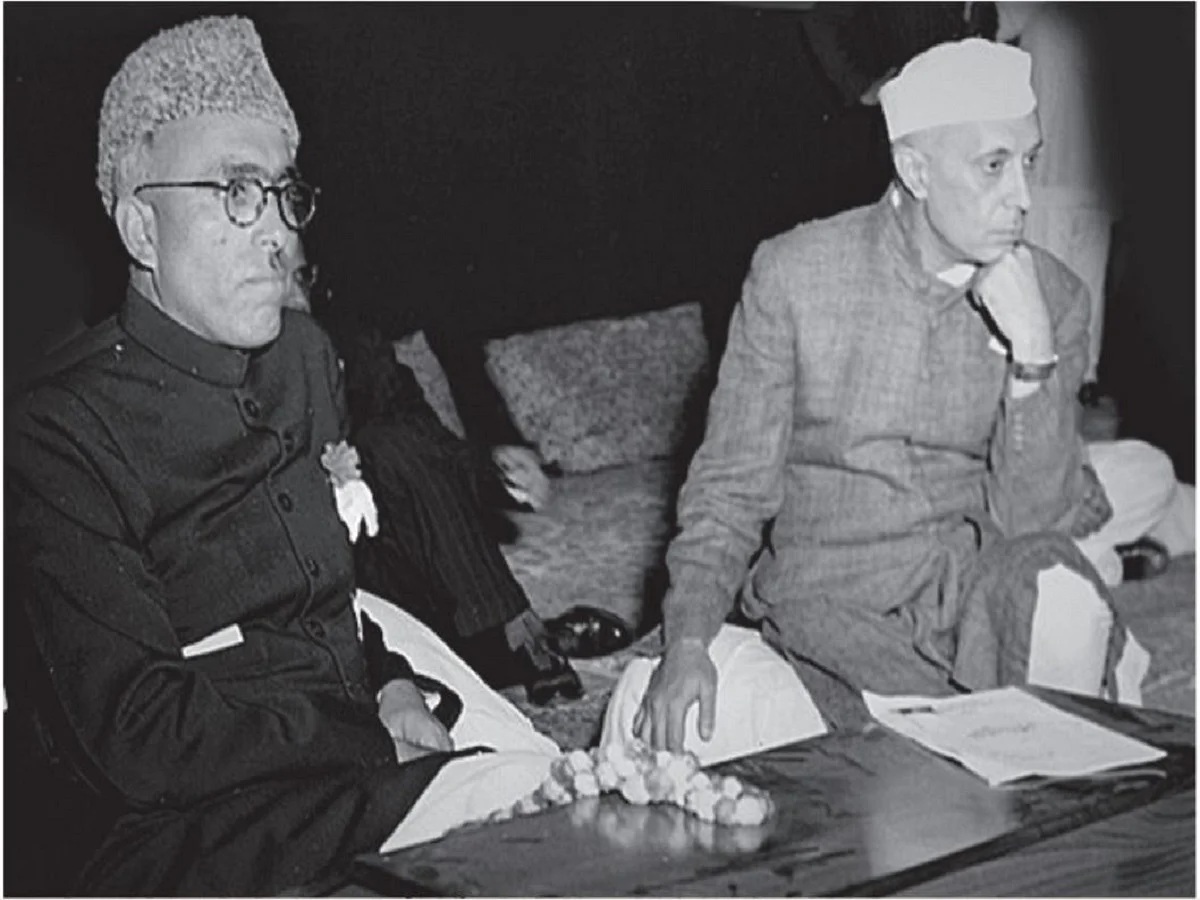

Friends who turned into foes post 1947

Friends who turned into foes post 1947

The third challenge for the Maharaja facing the political uprising in his backyard was to decide the accession of Jammu and Kashmir as the August 1947 drew closer.

“When critical decisions had to be made, the maharaja did nothing,” writes Victoria. “Hari Singh, however, never seemed to have given the future of his state nor indeed the subcontinent the consideration it deserved.”

The monarch appeared to be a helpless figure caught up in a changing world order, with which he was unable to keep pace.

In the interim, the Indian Independence Act was passed on 18 July stating that independence would be affected on an earlier date than previously anticipated: 15 August 1947.

The sense of urgency was heightened by civil disturbances, riots between the communities, which had reached Punjab bordering Jammu and Kashmir.

Meanwhile, Abdullah’s imprisonment had annoyed Nehru. He affirmed Abdullah being a local could handle Kashmir and made several attempts to meet him in prison but he was barred by Hari Singh.

In the summer of 1947, Nehru again planned to visit the valley to see Abdullah in prison. But given the troubling situation, Lord Mountbatten was reluctant to either send Nehru or Gandhi to Kashmir.

After careful deliberation, the last British viceroy of India decided to take up a long-standing invitation from Hari Singh to visit Kashmir himself.

On 18 June 1947, Mountbatten reached Srinagar and was straightaway snubbed by the unwilling Maharaja. He wanted to discuss Kashmir accession with the monarch who instead sent him on a fishing expedition.

The viceroy was told that the king would consult his people and meet him the next day. But the meeting was cancelled before 10 minutes of the scheduled time. Citing sickness, Singh said he didn’t want to meet Mountbatten again.

Later the viceroy understood that the king didn’t want to not join either of the dominions, till Pakistan’s constituent assembly was formed and the situation gets a bit clear.

Following the viceroy’s fruitless valley trip, his chief of staff, Lord Hasting Ismay, received the same treatment when he visited Kashmir to break the ice with the reluctant regal.

At the end of July 1947, Mountbatten heard Nehru’s eagerness and obsession for Kashmir. Nehru had even wept in front of the viceroy over the valley.

But instead of Nehru, Gandhi left for Srinagar as an emissary on 1 August 1947, and faced mass demonstrations. Even the windowpanes of his vehicle were smashed by protestors.

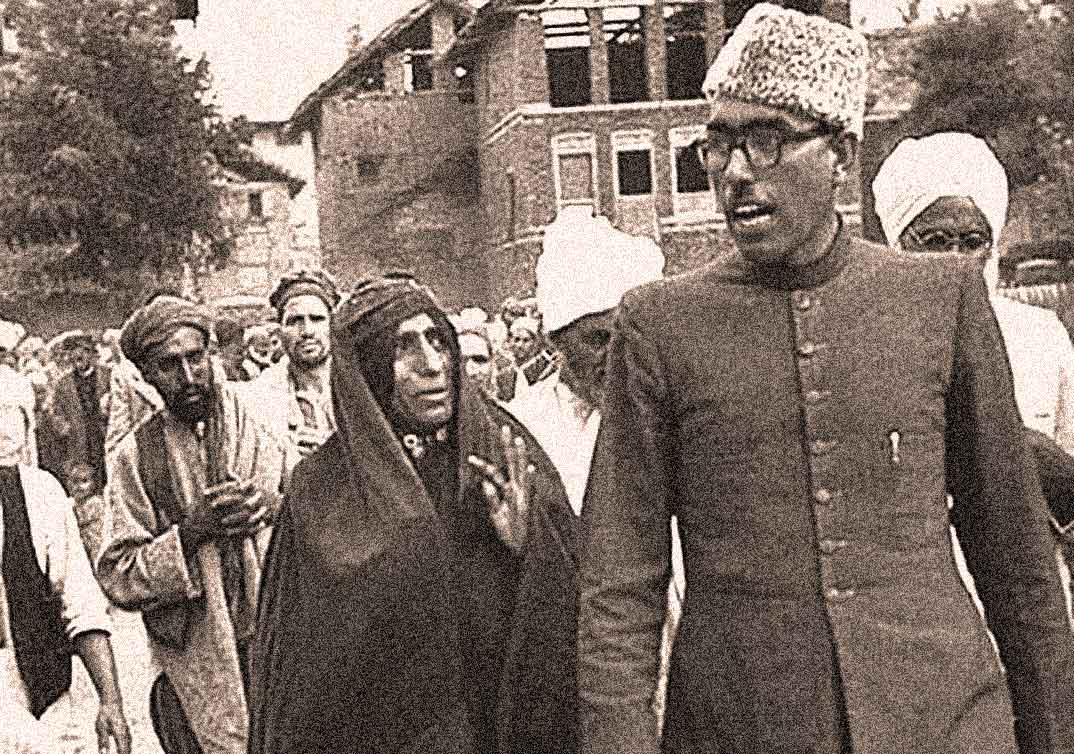

Abdullah led an anti-dogra campaign in Kashmir before 1947

Abdullah led an anti-dogra campaign in Kashmir before 1947

Despite the D-Day approaching fast and fanning tensions in the winter capital of J&K, Hari Singh remained dithering. As per his son, Karan Singh, the regal’s reluctance came from his prime minister, Ram Chandra Kak—the Kashmiri Pandit who wanted the sovereign to adhere to status quo.

But a day after India’s Independence Day, Hari Singh sacked PM Kak and got him replaced by a retired army officer. The king was now talking to hold a referendum in the state to decide whether to join India or Pakistan.

In the meantime, communal riots were decimating lives in the subcontinent. The killing took place when millions of Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs were crossing the border as per British designed demarcation of newly created nations.

The partition bloodshed reached the plains of Jammu in the fall of 1947 and reportedly left 237000 Muslims dead. The communal slaughter didn’t reach Kashmir because of its mountainous isolation.

Singh tried to remain sovereign for two months after the independence of India and Pakistan but the Poonch revolt, Jammu massacre and tribal invasion changed his guards.

Five days after the Jammu Massacre, tribals invaded Kashmir and in dilemma, Hari Singh sought military support from India on 24 October 1947.

Mountbatten had contended that it would be folly to send troops to the state without legal formalities of temporary accession before ‘a referendum / plebiscite’.

But as per Nehru’s biographer, Sarvepalli Gopal, at the meeting, “neither Nehru nor Patel attached any importance to Mountbatten’s insistence on temporary accession”.

Finally, in the bloodcurdling fall of 1947, the Maharaja left the mountains unceremoniously—and died as an Indian citizen on 26 April 1961 in Mumbai.

Hari Singh's Statue In Jammu

Hari Singh's Statue In Jammu

Years later, as his adversary would be shunted out by the BJP and its affiliates, the forgotten king would make a comeback in his erstwhile dominion, first as a statue and then a holiday.